Internships summary

Published:

Internships Summary

During my academic journey, I had the opportunity to participate in four impactful internships. Here is an overview of each internship (for a short version look at my CV):

- Dynamics and kinetics of heterochromatin

- Supervisors : Dr. Genevieve Thon & Dr. Kim Sneppen

- Location : Dpt of Biology - University of Copenhagen (Copenhagen)

- Duration: Spring and Summer 2024

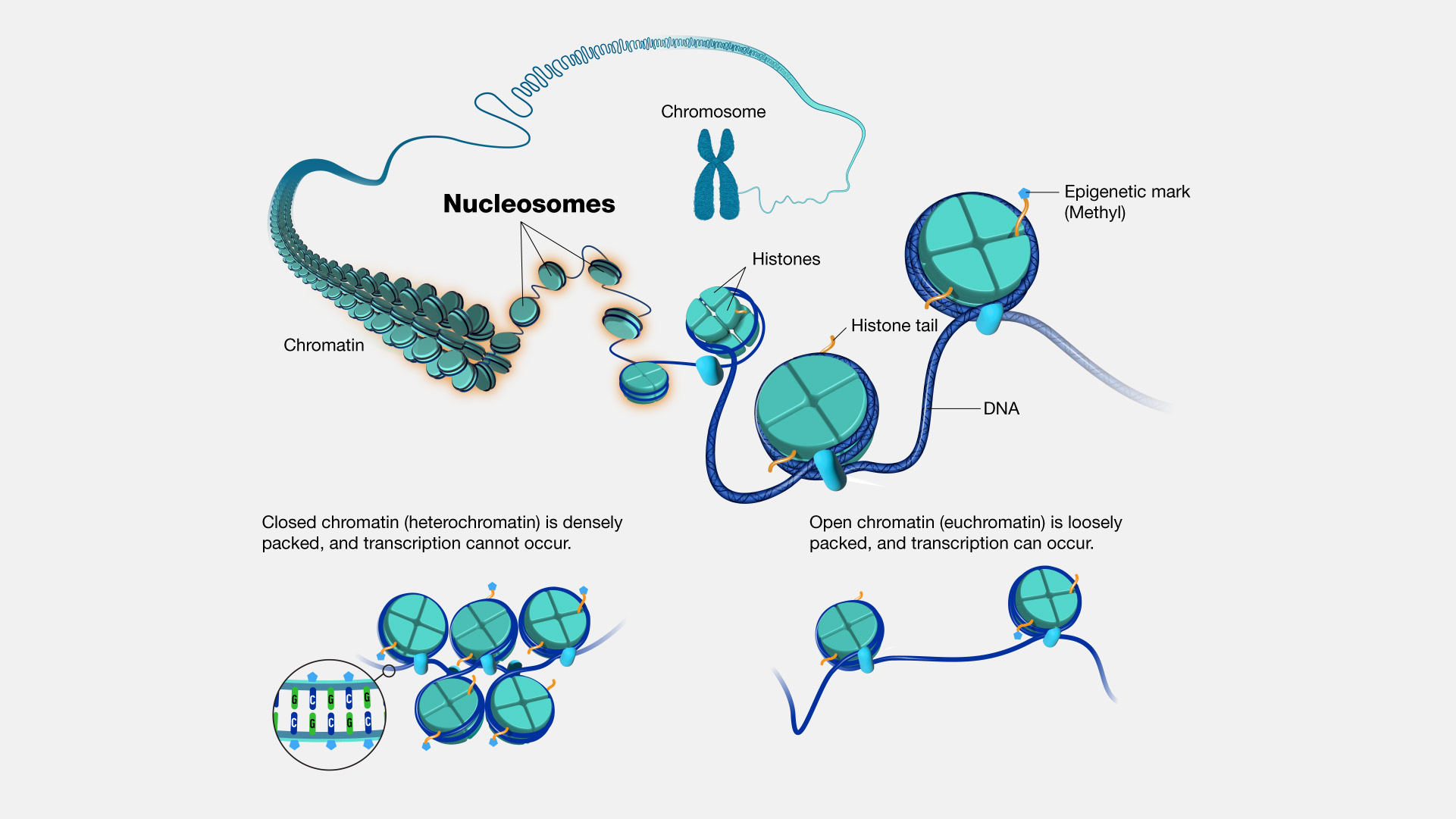

Description: As you may know, DNA is not linear in living cells : it is packed. Otherwise, it would be VERY long - $6.10^9$ base pairs with approximatively $3.10^{-10}$ m between each resulting almost 2 meters for ONE human cell! Nature as then adapt different ways to store all of this information (and for other evolutionnary “reasons”) through compaction at different levels. The one that everyone knows is the chromosome, the last entity that can be seen through a middle school microscope. But before that there is what is called the chromatin. Chromatin is the first degree of compaction of the DNA. The long DNA sequence is wrapped around proteins called histones and those complexes are called nucleosomes (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 - Chromatin to Chromosome by Daniel A. Gilchristn

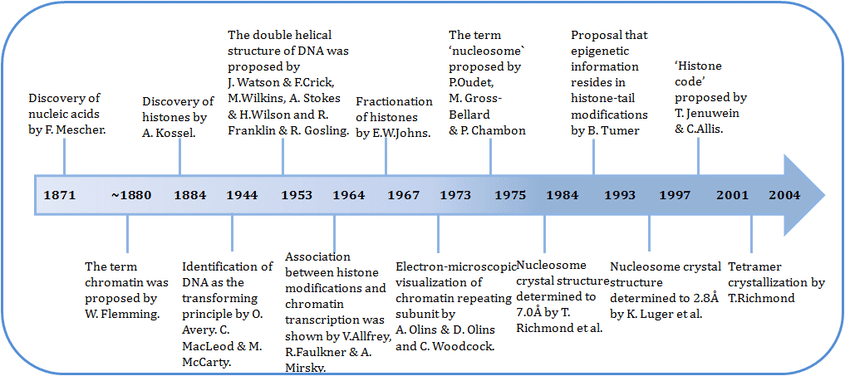

Figure 1.1 - Chromatin to Chromosome by Daniel A. GilchristnThe chromatin is known since the late 19th century but was mostly studied, as the genome structure, during the middle of the 20th century (see Figure 1.2 for the history of chromatin).

Figure 1.2 - Diagram of major discoveries about chromatin by Ramachandran Boopathi

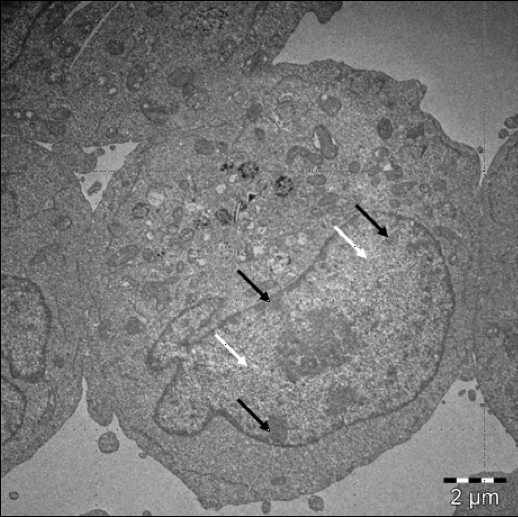

Figure 1.2 - Diagram of major discoveries about chromatin by Ramachandran BoopathiThe chromatin is mostly in two states : euchromatin and heterochromatin. The first one means that it is light under electron microscopy and the second is dark under the same tool (see Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3 - “ Electron microscopy image showing the classical dichotomy between euchromatin and heterochromatin in a human leucocyte. Most of heterochromatin (black arrows) is in the periphery of the nucleus, for the most part tightly attached to the lamina, while euchromatin (space pointed by the white arrows) is filling most of the nucleus space, without touching lamina. Image courtesy: Wioleta Dudka”

Figure 1.3 - “ Electron microscopy image showing the classical dichotomy between euchromatin and heterochromatin in a human leucocyte. Most of heterochromatin (black arrows) is in the periphery of the nucleus, for the most part tightly attached to the lamina, while euchromatin (space pointed by the white arrows) is filling most of the nucleus space, without touching lamina. Image courtesy: Wioleta Dudka”At the first sight, one might say that heterochromatin is more compacted than euchromatin because of that. But the compaction degree of hetero/euchromatin is still unclear. Indeed, it is a 3D polymer which is dynamic. It’s “biological essence” can’t be depicted through one image.

Another way to look at it is through the scope of genetic information, specifically epigenetics. If you are not familiar with epigenetics, I suggest reading the article “Epigenetics: The Origin and Evolution of a Fashionable Topic” by Ute Deichmann in Developmental Biology (416: 249-254). In summary, the term “epigenetics” was coined by embryologist Conrad Waddington in 1942, but it builds upon ideas from the 17th century. Although it followed the genetic revolution of the mid-20th century, epigenetics has become a significant field of study in its own right. It started to grow after the operon model of Jacob and Monod in 1961, two french biologists who got the Nobel Prize in Medicine and Physiology for their research in 1965. Epigenetics is defined by the Cambridge dictionnary as “a branch of genetics that studies the chemical reactions that turn genes on and off”. The main questions that arise then are : How are genes turned on and off ? Is it heritable through cell division ? Is it heritable after reproduction ? To study that kind of questions the model organism is the fission yeast or schizosaccharomyces pombe. Unicellular organism, this yeast has still the same kind of regulatory pathways of gene expression and DNA repair. Another way to study those questions is through coarse-grained modeling. [TO COMPLETE]

To look at the dynamics of heterochromatin, its behavior, its nucleation, its spreading (local or global or both), the effect of environmental parameters within the cell or the genome, the polymeric effect of chromatin on itself (coiled transition for example), the effect of proteins on the modification of histones through liquid-liquid phase separation for example (and a lot of other interesting scientific questions) I did the following :

- Model and simulate in 1D the chromatin with local and global changes, transcription and replication effects using Python from scratch (see GitHub - replication of the results of a previous article by Kim Sneppen, 2007)

- Model and simulate in 3D the chromatin with global changes using Reactive Molecular Dynamics with LAMMPS and the REACTOR package modified especially for this project by Jacob Gissinger.

- Molecular and cellular biology experiments (ongoing)

- Creation, with a PhD Student, of a Journal Club about phase separation in biology (mostly about LLPS, DNA repair and heterochromatin)

- Weekly lab meeting/journal club with Genevieve Thon’s team about chromatin dynamics and gene expression in fission yeast

- Daily meeting with Genevieve Thon

- Weekly meeting with Kim Sneppen

- Assisting to conferences and seminars both at the Biology Center and at Niels Bohr Institute (Physics Department of UCPH)

- Experimental study of swarming behavior of pseudomonas aeruginosa

- Supervisor : Dr. Maxime Deforet

- Location : Laboratoire Jean Perrin - Sorbonne Université (Paris)

- Duration: End of spring and Summer 2023

Description: Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a pathogenic bacteria for humans in the case of immunodeficiency. It is the third bacteria responsible for nosocomial infections. It is interesting to understand its development capacity and a specific type of motility: swarming. This motility, specific to bacteria, is the emergence of collective movement within a bacterial colony, based on various physical effects such as the Marangoni effect through the production of surfactants by bacteria: rhamnolipids. From a fundamental point of view, it is interesting to understand, at different scales, the emergence of collective movement with individuals that do not have direct awareness of their environment, but only through physicochemical effects. This ability allows bacteria to understand their surroundings, including their density. The goal of this internship was to create a multi-scale dynamic atlas - mapping - of swarming in p.aeruginosa using optical microscopy. This was done to quantitatively understand and analyze the internal activity within the population of bacteria through MSD calculation using fluorescence. The characterization of polymers produced during swarming in one of the mutants used, which may influence internal mobility by changing the viscoelastic properties of the environment, constituted the second part of the internship. [TO COMPLETE]

- Link to french report Internship LJP by Adrien Berard 2023

- Multiparamaters’ evaluation of cardiac dynamic using ultra-fast echocardiography

- Supervisors : Dr. Mathieu Pernot & Dr. Olivier Pedreira

- Location : Physics for Medicine lab - ESPCI (Paris)

- Duration: Fall 2022

- Description: [brief description of the internship project and tasks]

- Link to french report Internship Physics for Medicin by Adrien Berard 2022

- Molecular dynamics simulation of a minimal elastic catalyst model

- Supervisors : Dr. Olivier Rivoire & Dr. Maitane Munoz Basagoiti

- Location : Centre Interdisicplinaire de Rechercher en Biologie - Collège de France (Paris)

- Duration: Fall 2021

- Description:

The acceleration of a reaction’s velocity by the matter itself is something remarkable. This property is called catalysis. It occurs thanks to a reactant that is not consumed during the reaction. One example is fumarase, an enzyme involved in the Krebs cycle, with a rate constant close to $10^9 s^{-1} M^{-1}$. Catalysis only affects the reaction kinetics while preserving its thermodynamic properties; the reaction’s thermodynamic constant remains unchanged.

Catalysis has been extensively studied in chemistry for its industrial applications, whether in homogeneous or heterogeneous catalysis. A fundamental example of the importance of catalysis in industry is the Haber-Bosch process, one of the most widely used processes globally for synthesizing ammonia. Indeed, the spontaneous reaction is very slow because it requires breaking the triple covalent bond of nitrogen. A catalyst, specifically iron oxide, accelerates the reaction of nitrogen hydrogenation into ammonia. This catalytic process is crucial in the production of nitrogen fertilizers widely used in agriculture. The discovery of this catalytic process at the beginning of the 20th century revolutionized fertilizer production and thus food production, which likely would not have been as significant without it. Don’t forget though that Fritz Haber is considered as the “father of chemical warfare”… Catalysis has also been studied in biology for enzymatic catalysis. An example is beta-galactosidase, which facilitates lactose digestion in humans.

The effectiveness of catalysis is due to the interaction between the catalyst and the substrate, which must be “just right,” according to Paul Sabatier. Indeed, according to the principle named after him, if the interaction is too weak, the substrate will not bind to the catalyst, resulting in no catalysis. Whereas if the interaction is too strong, the substrate will not detach from the catalyst, also resulting in no catalysis.

The mechanism of catalysis is poorly understood from a physical perspective. Basic questions, whether regarding the constraints and limitations of this phenomenon or its connection to material properties, still lack answers. Indeed, a comprehensive physical general model of catalysis has not yet been formulated.

Studies on enzyme functioning can be approached in various ways. One can study a specific enzyme, conduct directed evolution to mimic natural selection (Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2018 for Frances H. Arnold), or perform ab initio calculations to predict the enzyme’s or a heterogeneous catalyst’s structure. To study their catalytic activity, two commonly used methods are found. On one side, there’s mathematical formalism with Transition State Theory (TST). This approach to chemical reaction studies examines the reaction’s kinetic constant as well as potential energy surfaces. On the other side, there are molecular simulations specific to a particular catalyst to have a complete description of the system. While this approach is too detailed to draw general conclusions, the former lacks the necessary details to understand the geometric constraints giving rise to catalysis.

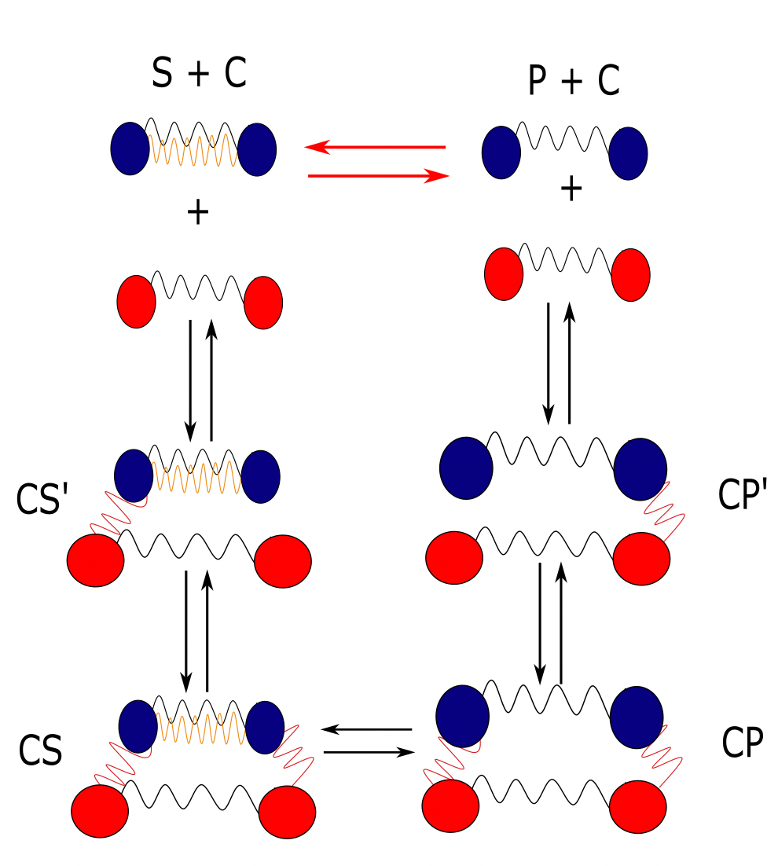

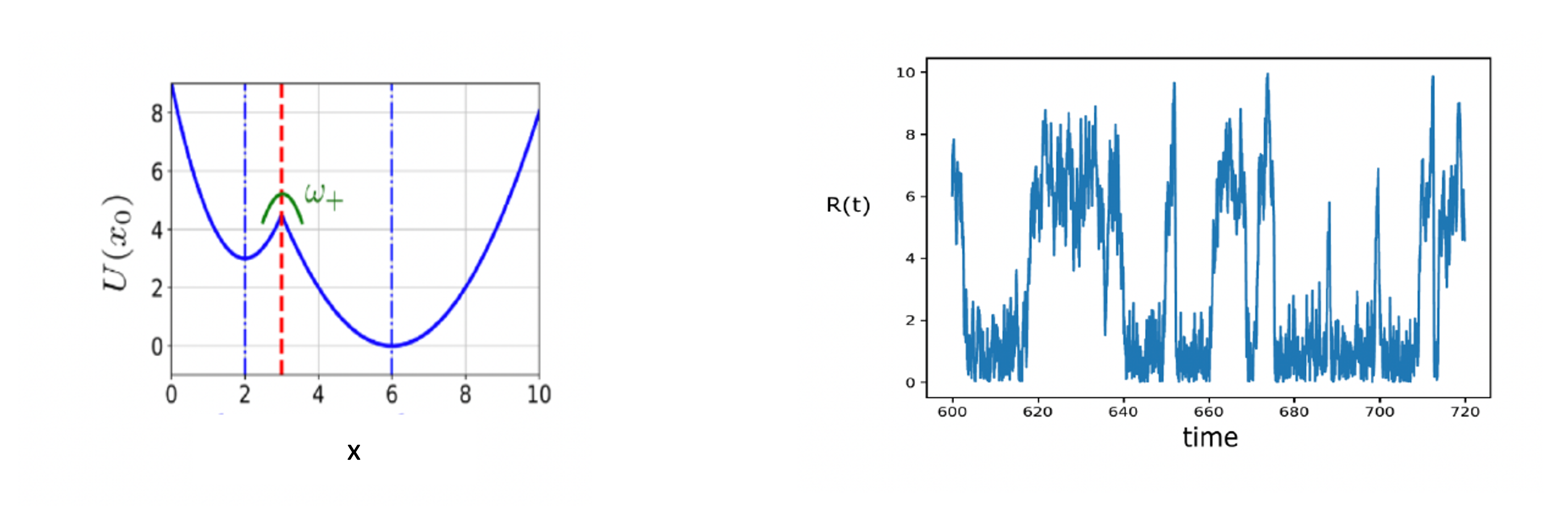

This project continues from an article by my internship supervisor, Olivier Rivoire. He chose to describe catalysis through an elastic network. The particles in this model are point-like. From this model, we will attempt to answer the following question: For a given type of reaction and under certain conditions, what is the simplest and most effective catalyst possible? Thus, the aim of my internship is to combine the theoretical approach of TST and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, which I will explain further below. We will conduct Langevin dynamics simulations of the one-dimensional elastic network model presented in figure 4.1, where we know catalytic solutions exist, without assuming anything about the transitions in the system. Transition rates arise from dynamics. The objective is to test the parameter sets found by Olivier Rivoire under different reaction conditions and verify catalytic activity. My project aims to bridge these two approaches using a coarse-grained model, a simplified model, of catalysis. This model must be detailed enough to consider the geometry and catalytic properties of the object but general enough to understand this phenomenon from a fundamental perspective.

to do :

Décrire l’équation de Langevin $m\frac{dv}{dt} = …$

Décrire la dynamique moléculaire

Movie 4.1 - MD Simulation of 20 particles in a periodic box using Langevin equation, Verlet algorithm and NVT ensemble.

- Décrire le potentiel de Lennard-Jones

- décrire le modèle élastique

Figure 4.2 - Elastic catalyst model by Olivier Rivoire - graphic realised with InkScape by Adrien Berard.

Figure 4.2 - Elastic catalyst model by Olivier Rivoire - graphic realised with InkScape by Adrien Berard.  Figure 4.3 - Elastic catalyst model by Olivier Rivoire - Kramers escape problem with two wells and its realisation using MD simulations

Figure 4.3 - Elastic catalyst model by Olivier Rivoire - Kramers escape problem with two wells and its realisation using MD simulations

If you want more information, please do not hesitate to contact me.